Two very good follow up threads. @willowleaf pointed out the almost comical assertion that little women need little boats. Objectively, the primary purpose of a boat is that it floats; every other feature of the design is subjective, in that it basically influences seaworthiness, handling, comfort, stability, or load carrying characteristics. Ironically, the first question you might ask isn’t whether the kayak is tippy enough, yet so many discussions insist that the owner needs to get used to the instability. That’s reverse logic - if the goal is specific handling characteristics, instability might instead be considered a consequence the design rather than a desirable feature. My point being that the buyer should look for the boat that fills the requirements. The advantage of learning skills such as rolling, advanced paddling techniques, and the ability to enhance tracking and turning through edging is a plus, especially for the experience kayaker who demands precise control. If your only concern is floating to look at ducks, all you really need to be concerned with is displacement.

The first and minimum requirement is that the boat is buoyant, because it has to support the weight of the occupant, passengers or load, and it has to be effective in the conditions it was designed to operate in, no more no less. You can’t ignore the environment or you’ll be disappointed. The weight class of a kayak is a safety guide around which the designer shaped the performance characteristics. So the buyer has to consider how the kayak will be used. While freeboard improves seaworthiness (reduces water splashing into the boat from high seas), any amount of boat above the water will catch wind. The main difference between a kayak and a canoe of the same length is a closed deck vs. open deck, then the typical canoe will be wider with greater load capacity. Otherwise, they’re both still displacement boats.

There is no one style fits all, or one design that handles all conditions. If your pleasure is tackling conditions that require nimbleness, you’ll seek rockered boats; your physical dimensions of weight, height, girth or shoe size mandates certain design parameters. A slightly built person can adapt to a large boat better than a large person can fits a small boat, but that doesn’t mean that either extreme will perform optimally or safely.

A recurring topic ponders the reason why interest in sea kayaking or kayaking in general is waning. I personally witnesses a proliferation of rec kayaks, then sea kayaks. At the peak, rental businesses offered a wide range of recreation, touring and sea kayaks. In the past few years, their stock has morphed to all sit-on-top varietys, and more recently, the shift has been to stock more Stand Up Paddle Boards. More anglers who previously adapted to a typical kayak have upgraded to dedicated fishing kayaks, because they have fittings for tackle and are more stable. The interest in water activity hasn’t changed as much as the style of watercraft. When I ask paddlers about the craft of choice, a recurring theme is a preference for a more stable boat and the feared of being trapped in a tippy kayak with a tight cockpit. I wonder what message the average person would carry away, after reading advice from the forum.

The predominate design feature hinges on displacement. A 145 lb paddler needs a kayak designed to carry that weight, as does a 245 lb person. Buoyancy requires a specific area that displaces “X” amount of water. While there are exceptions, based on my experience with the Tsunami line, my 13 yr old, 90 lb grand daughter graduated from a 10’ x 23" Perception Prodigy to a 120 Tsunami SP, 12’ x 21" x 12" deck, which offers the freeboard to handle some relatively rough condition and still remain dry. In that boat, she can paddle 7 miles at 3.11 mph avg speed. Anything larger and she probably wouldn’t have the physical strength to handle the length. However, the 21" width is more than stable for her weight, size and reach. Her sister has been using the 140 Tsunami (24" wide model), for the past 2 yrs and has no problems controlling the size. I don’t have specific speed data for her, but she is approaching 4 mph avg over 7 mile distances with no complaints or stops.

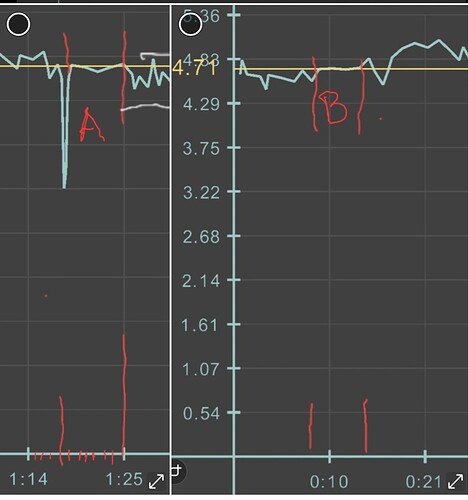

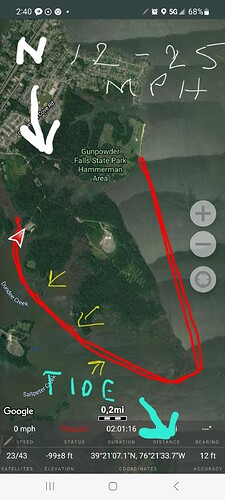

The latitude for the 140 Tsunami is about 120 lbs through 180 lbs. Outside of that range, the consensus of members of my family who tried it feel it’s either too hard to control or unstable, while the 145 lb paddler seeming to be the sweet spot. The proper displacement point for me at 235 lbs is a kayak that’s 17’6" x 24" wide (which offers at least 45 lbs extra load, compared to a 65 lb surplus for a 145 lb paddler in the 140, and a 54 lb surplus for a 90 lb paddler in the 12 ft kayak.). Based on feedback from my sister and grandaughters, the handling characteristics are similar across the models. I can attest to the relative performance capability of paddlers using the 12 ft, 14 ft, 14’6" and 17’6" Tsunamis, because each boat performs similarly except for speed, with the longer kayak being fastest. The avg speed bracket between 3.11 mph for a 13 yr old in a 12 ft, 4.4 mph for my sister in a 14 ft, to 5 mph for my personal avg in a 17’6" can be explained due to hull speed limit and physical ability.

One problem with comparing low volume to high volume in the same model is a matter of dispacement, proportion, balance and hull speed. No matter the design, a heavier paddler needs a larger boat which add a twist to the equation. The difference between the high recorded average speed by the named paddlers in the three boats tested is listed below:

12 ft=5.4 mph hull spd; 3.11 mph is 2.3 below hull spd

14 ft=5.8 mph hull spd; 4.4 mph is 1.4 below hull spd

17 ft=6.4 mph hull spd; 5.03 mph is 1.4 below hull spd*

*note: The best average speed using the 145 Tunami, from two year ago, was 4.84 mph, which is 1.06 mph under the 5.9 mph hull speed, which suggest it may be comparitvelly faster for the length, and I get that impression when paddling it.

While the method of calculating hull speed can be argued (the dimensions used to calculat hull lenth is the overall length vs. length on the load water line), yet the implication of this raw data is interesting. My grand daughter’s avg speed is 1.89 mph slower than my average speed, but realize that the 12 ft hull speed is a full mph slower than the 175 Tsunami. After factoring in hull speed penalties, for what it’s worth, she is only .4 mph behind my sister, and .89 mph behind me. Also, when considering that hull length favors speed, my sister isn’t far behind me when she is similarly conditioned; her best speeds nearly match my output if the limitations of the hull speed is factored in.

There it is @willowleaf! There are many variables that aren’t contolled, but I believe you are correct in thinking women (perhap even those within a wide age range) can be just as capable if properly fitted in a proper boat (if you didn’t imply that, I will). @szihn and I discussed that topic and independently arrived at a similar conclusion.

Another question that comes to mind is what part drag plays in the equation, because the difference in displacement can’t be factored out, even if every other design parameter is followed:

120 Tsunami SP: 90 lbs/40 lbs = 130 lbs (---- gals)

140 Tsunami: 145 lbs/57 lbs = 202 lbs (8.6 gals)

175 Tsunami: 235 lbs/69 lbs = 304 lbs (20.9.gals)*

Combining the weight of paddler/boat, using the SP as the baseline, the difference in displacement is shown in gallons. Nothing in the design that I can think of can compensate for that increased drag. My point isn’t to show any scientific conclusion, but this is the first time I did a cross comparison between the different boats. It made me think, calculate, and realize that the people I paddle with are far stronger paddlers than I realized. Or does it show any advantages due to specific hull dimensions or ratios. As a finishing thought, I can out sprint both of them, but their average speed is competitive with mine when you consider the limiting factors of the hull length and width.

I expressed disapointment with the WS decision to increase the width of both the 140 (24" to 25.5") and the 145 (24.5 to 25.5). The previous design made sense, but now they only offer a 145 model and a second model that’s 6 inches shorter. The real problem for a person who is smaller in stature is excessive width. A more rational decision may have been to offer a 14.0’ x 23.5" version, because I think it would have been just as stable as the other models and proportionally faster. We’ll never know.

![]() Unless you’re rock gardening and surfing…but even then, you’d actually be better off in a whitewater kayak.

Unless you’re rock gardening and surfing…but even then, you’d actually be better off in a whitewater kayak.![]() I’m a big believer in different branches of paddlesports adopting techniques from one another…and I think sea kayakers can learn a lot about paddling technique from whitewater paddlers.

I’m a big believer in different branches of paddlesports adopting techniques from one another…and I think sea kayakers can learn a lot about paddling technique from whitewater paddlers. ![]()

![]()