So for years I’ve owned a Wilderness Systems Tsunami 165. The Tsunami is probably one of (if not the) most widely varied lines of any single kayak in history. Over the years there has been a Tsunami 120, 125, 130, 135, 145, 165, and 175. That’s a lot of models for one kayak design!

It goes without saying that these are not all the same boat. In fact, it would be fascinating to line every different Tsunami that was ever made up next to each other and do detailed measurement comparisons. But how similar are all these boats—beyond the name “Tsunami?”

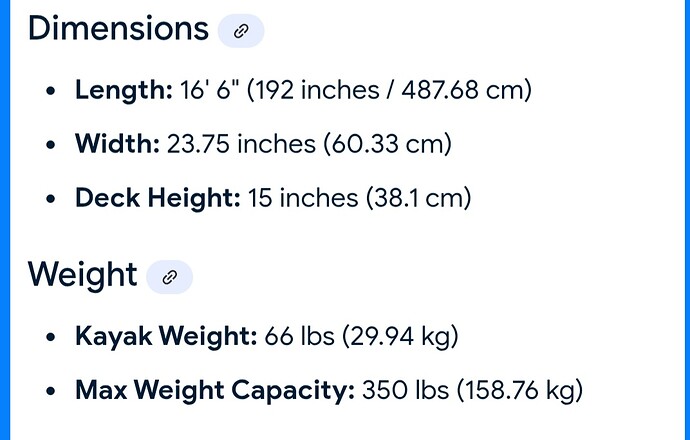

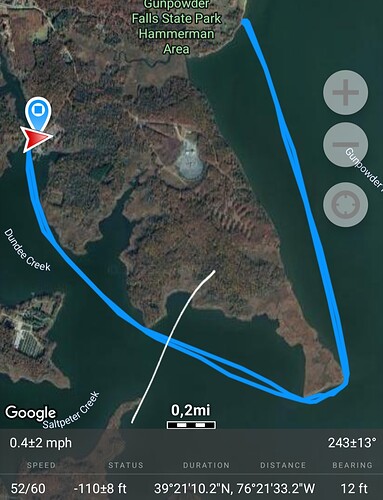

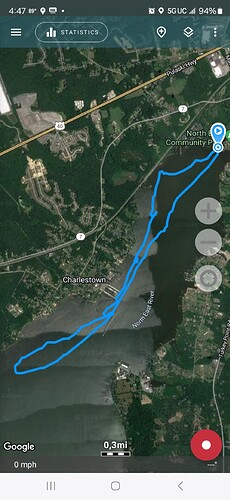

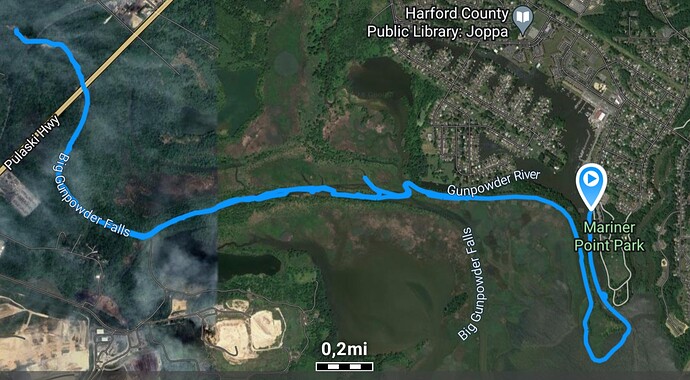

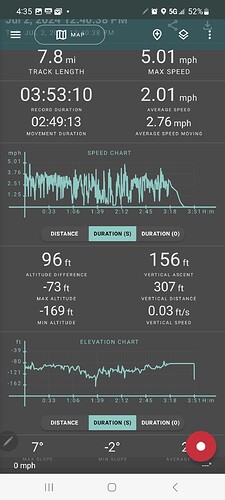

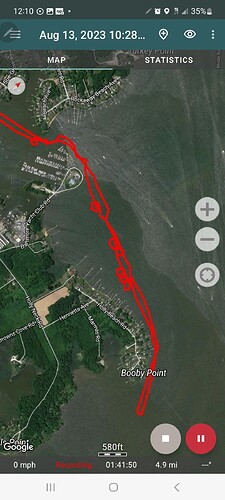

My question is prompted because I recently bought a second-hand Tsunami 175 (17-1/2 feet long). For some reason, before buying this boat, I assumed it would be identical to my Tsunami 165…but 6 inches longer at either end and capable of carrying 50lbs more gear. I’ve only paddled it one time so far (for about 5 miles in calm conditions)…and my initial impression is that the 175 is a very different kayak than the 165.

The first thing I noticed is that the entire cockpit area feels significantly larger than the 165 (which is already roomy). I’m 5’10" and 210lbs, and I felt like I was swimming around in the 175’s enormous cockpit. The next thing I noticed is that (possibly because the deck right in front of the cockpit feels higher), the tip of the bow feels much lower than it does in the 165. In other words, in the 165, you feel as though the bow is higher (more upswept?) and rides better over waves. In the 175, the bow feels lower, and closer to the water…so tends to go through waves rather than over them.

This got me thinking about how boat designers take one model of kayak and modify it to be bigger or smaller, and/or to suit larger or smaller paddlers. Is there a “right” way to do this? Is it even possible without essentially designing a totally different kayak? Other questions on my mind are…

Do you simply take the smaller boat and reproduce it exactly…then just extend its length without changing anything else?

Do you scale the boat’s dimensions up or down in every direction until you have the desired length?

Do you just change the size of the cockpit while leaving the rest of the boat the same?

I’m sure the answer is some variation of “It depends on your goal.” I also wonder, do kayak designers actually build working prototypes and test them on the water at different sizes with different-sized paddlers? Are there boatbuilding formulas they know that can provide most of the answers?

My assumption is that designing a kayak is as much art as science. In the case of the Tsunami 175 versus the 165, I have this nagging feeling that the 175 is not a “well-scaled” version of the 165, and that perhaps a few less-than-ideal design decisions were made. Which doesn’t make the 175 a bad kayak…just that it feels like a very different kayak—perhaps not even deserving of the “Tsunami” name.

Because when you give several kayaks of different sizes the same name…it’s reasonable for people to expect that the basic characteristics of that kayak will remain the same.

If anyone has any knowledge about how kayak designers scale a given design up or down, I’d love to be enlightened!