When a current moves in opposition to wind and/or waves, conditions become much rougher – often rough enough to capsize large motorboats and easily overwhelm small, human-powered craft like canoes, kayaks, and paddleboards. This National Center for Cold Water Safety video examines the danger and explains where it commonly occurs so you can avoid getting into trouble.

For more information on cold water safety, visit www.coldwatersafety.org

I love how the first video showing the “dangers” looks like an absolute blast.

But yeah, I wouldn’t play around in that water unless I had an open deck boat or was way experienced with a roll.

This can happen in a less dramatic fashion even on inland rivers but sometimes serious enough to cause problems for less prepared kayakers.

I most often paddle on a major river (the Monongahela) that i can launch into 15 minutes from home. The Mon is part of the Mississippi system and joins the Allegheny to become the Ohio before proceeding to the Mighty Miss. It’s a wide deep “industrial” river that flows in broad curves through deep valleys and is fairly level due to a series of large dams. But it flows basically west, which means it runs counter to the prevailing weather systems and the winds that blow east.

On windy days during periods of strong GPM flow in the Mon due to recent heavy rains I have often encountered confused wave lumpy water areas and even walls of standing waves with whitecaps due to the water/wind conflict especially in sections of the river with extensive sand bars beneath the surface due to the natural constant accretion zones along the shorelines and near midstream islands. I’ve seen people in rec boats get really tossed around and even capsized by these wild patches and mini-tsunamis (the capsizes usually appear to be panicked over-reactions by the paddlers). Because of the river’s twists and turns these conditions often only appear when a paddler has rounded a curve from a section with relatively protected and mild conditions into a more open west-oriented section of the river where the wind is directly battling the strong flow…

I don’t venture out on the Mon without checking the USGS gauges for the sections I plan to paddle and the projected wind speed for the day. Then again, I am always in a sea kayak that can handle waves.

A great video. It touches on many different scenarios besides just opposing wind and waves. Deception Pass, WA is a great example of tidal rips caused by large volumes of water moving through narrow channels. This place can give even large power boats trouble. Watch your tide table and run it at slack.

The Columbia Bar is famous for winds and opposing tides, but the large swells coming off the Pacific pile up in the shoals caused by the deposition of sediment carried by the huge volume of the Columbia.

I grew up on Chesapeake Bay and spent nearly every weekend for years in the area around Thomas Point Light and the Bay Bridge. Great examples of shoals and tides causing rips and waves. The wind just makes it worse. Once I was running a friends 17 foot power boat on a rough day. Instinctively I reduced power as we hit a really large wave. We took some green water over the bow. I will never forget it. Very embarrassing at the time.

In the salt water, always bring a tide table and understand how to read it and predict the currents that result. Sometimes you just have to wait on shore for an opportunity. It is like a chess game with Mother Nature.

Most of my paddling is on the Columbia River, but not at the mouth. That would take a crazy person. However, the stretch of water where I paddle does get the wind against the tide and it can get pretty bumpy at times. The neat thing is that you rarely get caught in a situation where you can’t quickly bale out of the waves if you need to. The waves almost always follow the river and don’t really go to shore. Another big plus is that the shore is almost always a nice sandy beach within a quarter mile, or so.

I did one time have to confront some waves that I had some apprehension about. I had to get back through them to get back to my launch site. It was summer and I had my skirt on and I figured what the heck. All the fishing boats and other small craft were long gone, so at least I wouldn’t have to watch for them. My first mistake was to go right straight into the waves. After two of them where I slammed down on the back side, I decided to revert to my sailing experience and try about a 45-degree angle up the face of the wave. In order for that to work, it required that I paddle only on the leeward side of the boat with an extra strong stroke just before topping the wave to keep from being blown off course. This all worked so well that I really thought about playing around in this stuff after I got back to my launch area. On second thought, I decided not to push it. Through that whole mess I never had one wave spill on top of me. I was almost completely dry when I went to shore.

I live in Rhode Island, but I am a river paddler not a sea kayaker (I know, makes no sense at all).

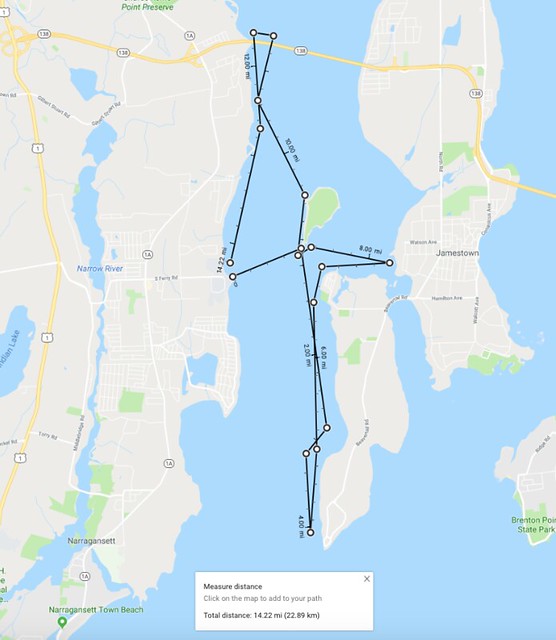

Anyway, one of my few sea kayaking trips was on the West Passage of Narragansett Bay. For those of you who know the area, we put in at the URI Bay Campus, crossed the West Passage to Dutch Island, headed south to Beavertail and then north to the Plum Beach Light.

I was paddling a 17’ Heritage sit-on-top sea kayak. It seemed a little tippy at first, but I got use to it. The tide as coming in and the wind was from the north, so we had the exact conditions described in the video - wind and waves from opposite directions. We had 1-2 -foot waves for the crossing and I was fine with that.

We then headed south toward Beavertail and the open water of Narragansett Bay. As we approached Beavertail, the waves increased to 3-4-feet with a following wind. The plan was to paddle around Beavertail, but when the guy I was with rose up on a big wave and then disappeared behind the swell, I wimped out and we turned around. If I dumped in those conditions I was afraid I wouldn’t be able to get back in the boat. Paddling back into the wind with following waves was even worse, but I made it.

The rest of the trip was great. Other than occasional rouge boat wake, waves were 1-2-feet and the wind was manageable. Amazing how quickly conditions can change. I’d say that the big weaves were more about paddling into the open water of Narragansett Bay, but the wind didn’t help.

The key is to understand your area, go with someone who is experienced and knows the area, or train in the skill needed to handle your boat in harsh conditions. Being trained only works if you understand your limitations.

I initially though the water flow in the Chesapeake Bay was consistent due to its width. This summer, I went out Rock fishing with by brother in his power boat. Between his depth finder and his GPS, the effect on the water surface was visible where the depth went from 30 feet to 7 feet. Speeds increased to 3 mph and waves formed.

Part of the thrill of kayaking is learning how the forces of tides, wind, water tempersture, water density and the constricting land mass work to shape the flow and the surface. The lakes formed by dams on the Susquehanna River are challenging and can easy go from flat in the morning to 12 or 18 inches within four hours as the wind develops during mid day, but bodies of water influenced by tidal forces can be like white water to a varying degree. Just the difference in water density creates turbulence, because salt water comes in on the bottom and the fresh water climbs on top.

My enjoyment comes from interpreting the conditions, and using the currents to advantage. I carry a VHF and check hourly for weather updates and alerts. It’s important to understand how far you are from land and how fast you can paddle, as well as how long you can put out maximum effort. Its critical to know how fast you can paddle and where you expect to run into counter currents, always. If you can paddle 5 mph, but find yourself going into a 3 mph current, when you’re 10 miles away from the launch, and you see dark clouds on the horizon, as NOAA alerts a marine advisory of a storm front moving at 30 mph. It’s 60 miles to the west, and you’re on the on the eastern shore. Do you stay and wait for it to pass or go for it. Know your limitations.

I hear you, Mountainpaddler. One persons blast is another’s nightmare. The line between excitement and a very frightening experience is often thin, and that’s why awareness of hazards is so important.

Thanks, Magooch, That’s the wonderful thing about having knowledge and experience like yours to draw on when conditions get pushy. It’s also interesting that this knowledge often scales well. Large bulk carriers over 1000 feet long often quarter into waves to avoid being slammed.

Thanks for your very informative comment, Jyak. Great info and really good examples. I agree that it’s not only important to gain this knowledge, it’s rewarding to apply it to actual paddling situations. It can be a very dynamic environment.

Good call, Eckilson. Nothing wrong with backing off the plan. It’s a sign of wisdom. It’s also not hard to see that rounding the southern tip of Dutch Island could be intimidating with large swells like that. Novices often fail to appreciate the way in which headlands or points concentrate wave energy, and I think conditions would only have gotten worse had you continued.

Thanks, Ppine. When those 20+ foot swells come rolling in to the Columbia River Bar, all hell can break loose. Like you, I spent a lot of time paddling around the Chesapeake Bay region. Thomas Point is a good example of a tricky area where conditions can morph with surprising speed. Now I’m living in Vancouver, WA on the Columbia River. Different scenarios, but similar dynamics. Just half an hour or so upriver is the Gorge - another place where the topography constricts the river and the wind. It’s well known as a playground for boardsailing, downwind ski runs etc. There’s a section at Hood River that can get truly ferocious under the right combo of wind against current. The experts love it when it gets really big, and the novices look and say “Oh, hell no!” It can be a very unforgiving place if you get separated from your paddlecraft and have to swim for shore. Photo taken on a really big day.

MoultonAvery, it was a good post that generated great replies. I think some newer member might hear the warnings from experience members and wonder if it’s a safe pastime. The points made show that its important for a each kayaker to make assessments of the his or her skill. It isn’t just a matter of having the physical ability to cover a distance, but it’s more important to analyze the personal level of skill to handle the environment. Paddling coastline isn’t the same as open water, even if there is no wind or waves

I always wanted to go to a town called Rock Hall on the opposite side of the Bay (few miles north of Thomas Point Light). Red line is 11.5 miles one way, which I can handle. So I set off, but turned around when I encountered 12 inch waves within 1/4 mile, because I knew the route crossed deep channels and shoals that would increase wave heights. I turned around, because if I got into trouble, it was at least 5 miles of open water in any direction. I regularly travel the yellow course which is 10 3/4 miles one way, but that course is never more than 1 1/2 miles from land at any point. So if I followed the black course, it’s 33 1/2 miles, of which I’m capable, but its approaching my maximum. The problem is that the return leg is north into the Bay outflow, so tides would have to be favorable, but the last third would be crossing the Bay at a constricted area. If I started to fatigue and ran into problems, I would drift toward the area I wanted to avoid.

I’m offering this to new paddlers, as an example that it isnt enough to just think you can cover the distance and physically handle it. Consider the water conditions and what you would do if things get sideways. Same applies to group trips. It may be safer with others, but there is no safety in just numbers, if you aren’t up to meeting the conditions you encounter.

Hi Jyak - Excellent points, every single one. Back in the late 80’s, my kayak partner, Brian Price, and I did an 18 mile winter crossing of Chesapeake Bay from Point Lookout to Smith Island. Spent the night and returned the next day when the weather was worse - blowing hard from the north with snow showers, beam and quartering seas. No cell phones, PLBs or portable VHF radios in those days so we were on our own. Saw no other vessels other than an Outward Bound sailboat that we towed off a shoal area in the Smith Island channel. (they had no engine). I think it took us around 6 hours to cross and we were out of sight of land most of the way. That kind of exposure can wear you down to a nub mentally if you aren’t comfortable in the conditions. We were very clear on the need to prepare well and be self-sufficient, because absent a miracle, there was no way anyone was going to rescue us if we got into trouble.

These are long crossings indeed. The Puget Sound near me is a narrower channel. I personally have never contemplated or imagined making a crossing longer than 2 or 3 miles (once I’m ready to go out there that is). Even within that constraint there are tons of opportunities here. Granted if there’s a spot with a very narrow channel the tidal currents would get rougher. But the distances across much of the lower or mid Puget Sound are not very long.

Speaking for myself, I don’t mind planning a trip. I plan things all the time, such as vacation trips that include the details of transportation, lodging, etc. so we are not stuck without a place to sleep one night, or have to walk or hitchhike long stretches carrying bags because I don’t know where the train stations are, or how to speak the local language, etc.

Then, some things go according to plan and some don’t. It all becomes part of the experience, and there is no need to feel like I “blew it” afterwards. I simply did my best and we had the best time that we could given the hand we ended up being dealt and the planning I did.

When people are excited about an activity, they want to do it. Training is good and can be important, but it shouldn’t feel like work. The person does some reasonable planning and skills training and then goes and does the activity. If this is not how an activity works, and it involves more pressure and stress, then it will not become popular and it will be a kind of fringe activity/sport.

Holly mackerel. I know the upper bay. The lower bay is out of my reach. No skill to manage the waters. Same bay, different water. The entrance to Baltimore harbor changes the dynamics. I’m good with that. If my grandkids want to do thst stuff, I’d earn the skills to go with them, but I’m happy with my level.

You hit the nail on the head. There shouldn’t be pressure. You need to want it. I sent the chart because it gives three options, each within my reach, two out for very important reasons. The yellow line I do all the time. By flowing the red line, it’s not much furtjer, maybe 2 miles, but the risk is far greater, if something goes wrong. The black route is longer, but it puts me in a choke point when I’m approaching limit. Because I traverse that area regularly, I know that I don’t want to risk the crossing unless everything is right. I’ve never been to Puget Sounds. It may be narrower, but from what I know of WI d and current. I wouldn’t even attempt that unless someone who knew the area paddled with me and assessed my ability. If that was area to paddle, I’d learn the skills and do it. I’m happy in the upper bay.

Lots of places to go. My daughter and her husband kayak and hike all over the country. They do t go out with me. Kayaking can be fun, it can be challenging, it can be a thrill. Figure how far you want to take it. I like the book I recommended to you about navigation. I want to know how fast I can go and how long I can endure it, because some day, the elements can be aligned against you and you need to make decisions. Bonking on a bicycle (once) and bonking in a boat (once) are very different. You stop on a bike. You drift out of control in a boat. Get to a place where you drift to land, vs open water

The Gorge championships week had 20-30mph winds all week, except race day (murphys law  )

)

On wednesday it was ripping a full 30mph against the current. Swell City, where your picture was taken, looked a lot like that. Easy 5-6’ swell (as in double overhead while sitting in a Ski).

That was the funnest day of paddling in my life. The swells were so perfect I felt super human. Normally with swell that large you struggle to get on it and surf, and the swell rolls away under you, stalling you on the back side.

That day the swell was so steep it just pushed you. I surfed through Swell City and hit every 10th stroke just to maintain wave position.

The Go Pro on a 3’ mast really flattens things out, but the standout 1-2 miles of this run were 3-6’.

If you’re in the right boat and have the skills, wind against current is heaven on earth. In the wrong boat or skill set, you’ll see the devil in the wave face.

Here is a video taken by a friend in my group on either tuesday or wednesday that week

Damn!! After a run like that I would just say “Lord please, just take me now”.

Play time!!! That was some good long riding.

sing