I’ve been watching videos to try to pick up this answer but it still doesn’t seem clear to me:

When turning the powerface of the blade, what is the proper angle to set? I’ve seen some that appear to have the blade straight up and down and others that are slightly tilted.

If you utilize the “pitch” stroke, wherein you begin to rotate the paddle during the power phase, essentially an early “J”, then you don’t need to have an aggressive vertical blade push out at the end of the stroke, which may be a negative in that it could encourage dragging the paddle power stroke behind the hip. Beginners often tend to do an awkward aggressive push outward at the end of the “J”, thinking that is the “J”. While it may effect a correction to your direction, it is ugly and would be a very inefficient and tiringly sloppy stroke. As you probably know, turning your grip hand thumb away and downward will get you into the right position with the blade, but it does not have to go fully vertical, as that may take a lot of uncomfortable wrist manipulation and you end up with a rudder stroke. It could be a long day and you will hate performing the “'J”

On the other hand, If your next stroke to learn is the Canadian,as it is essentially an elongated “J” with recovery mainly underwater with a mostly horizontal blade slicing through, powerface toward the surface. In that case you don’t want to go full vertical with the blade at the end of power phase of your stroke for the same reasons.

I’m an advocate of the pitch stroke. Meaning the blade does not approach straight up and down. I actually think of it as a very short paddle drag with the blade catching just a bit of water just before the paddle leaves the water. Think of it as beginning to feather the paddle while it is in the water with the bottom edge of the blade scooping a small amount of water as the paddle exits the stroke. The top thumb rolls out but just down a tiny bit. This allows for a shorter stroke that can end right at your hip. The advantage of that is more power. Where you start the stroke- entry into water can also very just slightly and you can sneak in a little diagonal draw before going to the power stroke and ending with the J. These subtle corrections can be added to every stroke to help you go straight.

In an unexpected way this has all been bad for my kayaking. My strokes tend to have slight drags rather than clean exits. Old habits die hard even when you switch boats. I went to the modified J or pitch stroke because the rolling motion of the top hand on the traditional J was awkard and fatigueing and made for a longer correction (less power).

My paddling evolved from open boats to a ww c1. The need to drive the boat with power demanded short quick strokes. Whatever you do, make sure you have some core rotation going on. Conceptualize twisting at the waist with the lead shoulder facing the corrective part of the stroke (face the work). This will put you in a much better position regardless of how you roll your top wrist or thumb. I guess what I’m saying is, if you are struggling a bit with the J also consider your body in relationship to the stroke. I can’t think of anything more awkward then doing a full J with the blade pushing out while your shoulders and head are looking straight over the bow.

I am strictly a canoe paddler, so cannot speak to how kayaks are paddled.

To assist with performing torso rotation and a powerful stroke, I tell beginners to make a rectangle out of a line between shoulders, arms and paddle. Elbows change bend angle very little, if at all, during the entire stroke. If elbows bend noticeably, then you are “arm paddling” and will tire very quickly.

Are you tandem or solo? I’m asking because a tandem partner provides momentum so the amount of pry can be quite negligible in calm water if all your doing is making a minor correction every stroke or so.

In that case, as others have mentioned, make the correction right by your hip. You don’t need to push the blade past your hips. So, with the blade by your hip, the paddle is almost vertical. Just make a quick flick of the wrist and pry out just a little (maybe pry of the gunwale to ease the effort off your arm), release the blade from the water and you can recover to the catch in time with your bowmate.

Yes, I’m mostly solo padling at this point.

Wouldn’t it be easier and faster to switch sides rather than do a J?

Beginners often strive to crank that grip wrist down to get a vertical correction. Sometimes this is necessary as they do not immerse the whole paddle and have it really far back . With practice they learn the j is at the the hip and you can avoid cranking that wrist down with a palm roll when you can immerse the blade , The thumb down is just a nanosecond hold before the palm roll to thumbs up( the paddle does not move). With water time the j stroke becomes the pitch stroke and the angle changes as people become more adept at subtle movements

Of course racers will switch sides every x number of strokes. Efficient and fast, but far from elegant IMO. Paddling race hard on one side for more than a dozen or so strokes is tiring, so we switch to the other side partially for muscle rest, partially for directional control as needed. Drips fall into the boat wtith every “hut”. When you settle into paddling on one side for a time, you become efficient with your hip close to the gunwale, with a bit of a heel or tip over to that side. Switching for no apparent reason becomes awkward and unnecessary. Doing the J on one side allows for fine tuning directional control, and if you do it right, fast forward motion. The beauty of the J is it is the entry stroke for a number of other advanced pleasurable and easy control strokes. Switching sides for no apparent reason, other than being sloppy with zig zagging a course is far from a thing of beauty to see someone do. In my solo, I don’t believe my bow yaws more than 5 degrees from a straight line on any stroke (unless I want it to).

For sure, the J works great, but in a narrow solo canoe with a low seat, such as a Clipper Solitude, switching works beautifully. In fact, i liken the movement on the switch to paddling my SUP.

Amusing how we are biased… Hit and switch never works for me on a trip. I can do it well in a WildFire ( yes) with symmetrical and substantial rocker bow and stern . I get about eight strokes per side… I have to keep the plant and recovery as far ahead as possible to avoid yaw.

However my trips involve wildlife sightings… Hit and switch is like flail and sail… the wildlife is gone when it sees all that movement. The J is a good tool to use with an inwater recovery.

So many ways to paddle a canoe.

If you’re on a sight seeing paddle, at the end of the power stroke, turn the paddle parallel to the side of the canoe, rest the hand closest to the blade against the gunwale and do a slight rudder correction with the handle hand before the next stroke.

Hello Mountain paddler. So many here have given excellent suggestion and advice, oh sure, I’ll throw my two cents in as well.

Yknpdlr, and tdaniel, begin spot on, and the benefits of switch paddling are not to be dismissed.

Some of the differences you see in the videos are likely to be the influences of lake vs river paddling and the paddles that go with each. Lake paddling, a long slender beavertail, pure pleasure. That immediately brings to mind the deep sliding strokes and the Canadian, doing the J right along side of the boat.

River travel, white water, a nice big flat blade that will bang the bottom less, mayhaps a longer shaft in big white water (In the big wave trains or going over holes a long reach is nice, air strokes are the pits.)

Now for my two cents, I use every one of those strokes and I do not plan them out, it is what ever works best. There is no one stroke.

My usual boat is a 20’Clipper MacKenzie, 3’" of rocker, (I need to switch every 3 or 4 strokes) turns easily, floats high (shallow) allows me to carry up to 6 weeks of water and food. A 10 day or 2 week trip is a little one for me. (Another reason for the large boat, think Yeti, Sasquatch, nearly as much fur and 300 pounds) (I stay out of the woods in the fall.)

I switch paddle all the flat stretches. Switch paddling is more efficient, fewer calories burned, annnd, switch paddling is an ESSENTIAL skill in white water. Cross arm paddling is bunk. Don’t bother. But, you have to be really good at switch paddling. The J with a beavertail, a placid lake, a lovely woman in the bow princess seat facing me, a Canadian is silent, effective, artistic, languid, everything you want for that lovely day , annnd in a lake with a crosswind, the paddle staying in the water reduces leeway by half. J’s can be at your side or well behind you, with a pry or no pry, or my modification the pry is against mine own hand, The shaft never bangs the gunwale.

The only stroke over looked here and I am a huge proponent of it… the gooney. Especially on a long trip, especially when reducing calories expended, especially if you have been a canoe junky for 60 years, my wrist would simply burst into flames from the friction generated heat if I tried to do 10,000 J-strokes in a 26 mile day. Do not do the gooney up and down right at your hip. Take a long stroke and put your thumb up wrist square to the paddle and the paddle the shaft length behind you in a rudder. That straight wrist and thumb up should be laid firmly across your midsection, your trailing arm at full straight extension and only the blade or half the blade in the water.

The canoe is to be loaded tomorrow morning, I am head the 2,000 miles west for the Green or Colorado, and then I have been promised to learn a new trick, a friend of my sister kayak surfs in Hawaii, I keep wondering if I can canoe surf, as if the waves in Big Drop 3 or Range Creek, or Lava are not big enough… And I will be doing the gooney.

Learn all the strokes and use what works best for that single stroke. You’ll be glad you did.

Perfect. Consciously chooosing which stroke variation to do should not occupy your mind. You do what is needed at the moment that experience in that boat simply works from muscle memory. Paddling is like riding a bike. When you approach a curve or a pothole on a bike, you don’t have to think precisely what maneuver you need, you just do it. If you work on perfecting strokes that naturally flow from one to another without thought, you then have total control over how you move through the water in your boat.

Regarding the gooney, it can have its place when a massive shift in yaw May be necessary, but it does not lend itself to smoothly doing much else from that configuration.

I never pry my finely tuned wood paddle against the gunwale. A gently perfomed J does not require it. Bill Mason was famous for doing so. If you note in some of his videos, at least one of his paddle shafts is almost worn in half from where he has slid it against the gunwale so many times.

yknpdlr:

I think you state it much more eloquently than I do. It does not occupy my mind. Well, sometimes a bit, when I am trying to be silent, or when I am trying to feel the grace of the stroke. I don’t sell the gooney short though, it is easy, very little pressure every other or every third stroke, no twist of the wrist. Again, I am often unaware. Sometimes I just drift, allow the current to do the work. Gaze about, listen for the small sounds, read a book.

Laughing, I take small and humourous issue with, “total control” , liking some white water as I do, I have been known to make a mistake or two. What a kind way of saying upside down and backwards and a sore arm from bailing the truant water from invading my space.

You have a great day, and just to make you jealous, I am signing off this AM, a canoe and gear to load, The Green and Colorado and then Hawaii,maybe the Colorado on the return, the soonest I’ll be back at my desk is about February.

I’m taking all this in. It’s clear that there are plenty of opportunities for nuance and maybe not as many hard and fast rules.

I like the idea of having a “conversation” with the water via your paddle.

I think that is the appeal for me with the canoe right now.

Thanks

I tell people when they ask do I fish along the way. I cain’t catcher no dang fishies. I can catch heck, catch a plane, catch cold, but completely inept when it comes to catching a fish or a woman. But, I also say “I can make a canoe paddle sing.” I like your word ‘conversation’. You will make a fine canoe paddler. I have many favourite stretches of river. If you are just coming into it, my first and highest suggestion is the Green River, beginning in Green River, Utah down to the Confluence with the Colorado. 120 miles, flat water, 10 days?, you MUST have made a reservation to be picked up by power boat to be hauled back upstream to Moab. Cataract Canyon begins just 2 miles downstream.

[quote=“Mountainpaddler, post:17, topic:112191, full:true”]

I’m taking all this in. It’s clear that there are plenty of opportunities for nuance and maybe not as many hard and fast rules.

I like the idea of having a “conversation” with the water via your paddle.

I think that is the appeal for me with the canoe right now.

Thanks

[/quote] One cardinal rule about maintaining canoe stability and yourself dry is to keep your head within the line of the gunwales.

However, a long established flatwater freestyle canoe instructor friend teaches to “get your heead in the water”. Not literally of course. Meaning that the feel of your hands on the paddle with your strokes and the connection to the water and the canoe all operate as one smoothly operating happy system. When you feel that, you will then “have your head in the water”.

Article I wrote about this topic, some time ago.

https://freestylecanoeing.com/jaded/

Jaded

The J-stroke reconsidered

By Marc Ornstein

When I first began canoeing, more years ago than I care to count, I was told that learning the J stroke was the holy grail to keeping the boat going straight. Over the decades since, I’ve found that notion to be almost universal with most instructional programs including it very early in the learning curve. The much easier to execute stern pry generally being frowned upon as inefficient and a symbol of poor technique. (An exception would be the whitewater community which prefers the stern pry for the added power it provides.)

While I agree that a properly done J is more efficient, the stern pry is far easier to master. For beginners, struggling to get their craft from point A to point B, teaching the stern pry first (along with hit & switch) makes far more sense. Despite this almost universal emphasis on teaching the J stroke as a basic, almost entry level skill, it is the exception rather than the rule to meet intermediate or even advanced level students who do it well.

Let’s begin with the name of the stroke, J. The proper path of the paddle doesn’t come close to resembling the letter J. If it did, each stroke would propel the boat forward during the catch and power phases then bring it nearly to a standstill during the correction (or J) phase. In fact, that is what I and my fellow instructors most often observe. If the paddle follows a J shaped path through the water, the last portion of the J is essentially a back stroke which is what we teach students to do when they need to stop the canoe while, in fact, our goal is to make a gentle course correction and to keep the canoe moving. We’d be better served by dropping the term “J stroke” and barring the adoption of some catchy new name, calling it what it is; a thumb down stern rudder or arguably a gentle thumb down stern pry. For now, I’ll simply refer to it as a thumb down, stern correction.

In an earlier article I described how to perform a proper/efficient forward stroke and that if done properly, very little correction is necessary. Unless one is fighting strong currents, winds or waves, only a small correction should be necessary to compensate for the yaw induced by the catch and power phase of the forward stroke. With that in mind, think gentle. Also, visualize a very mild rudder which softly guides the canoe as opposed to a hard push away or pry which forcefully deflects the stern. Finally, recalling basic high school science, think of the canoe as a lever with the fulcrum being near the center of the boat. If we want to pivot that lever, we need to apply some force either forward of or behind the fulcrum. The further away from the fulcrum that we apply that force, the less force that will be required. In this case, the force will be applied behind the fulcrum, near the stern. The further back (closer to the stern) it is applied the less force that will be necessary.

Now let’s describe the thumb down, stern correction (what we used to call the J).

● You’ve executed a forward stroke, being careful to keep the power phase short and straight with a vertical shaft. As the blade passes your knee, you minimize the power applied to it allowing it to essentially drift toward the stern (as the canoe moves forward). The blade has continued in a straight line. It has not followed the curvature of the hull.

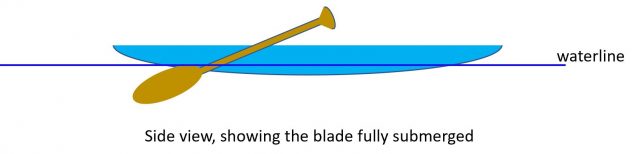

● As the blade is drifting toward the stern you are rotating the grip so that the thumb of your grip hand is pointing downward. By the time your grip hand has reached your hip (or nearly so) the blade is nearly vertical and perpendicular to the surface of the water. Keep the blade fully or near fully submerged. The grip remains low, just a bit above the gunwale.

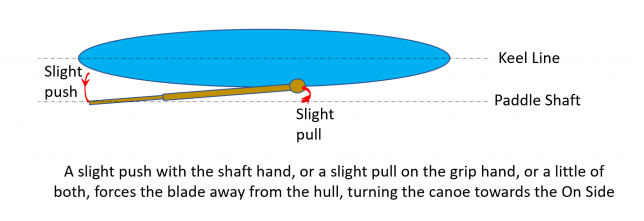

● Now bring the grip a bit inward, toward your hip or push your shaft hand outward slightly or a combination of the two. Either will create a slight angle with the tip of the blade a bit farther away from the boat than the grip end. The blade has now become a rudder, nudging the stern away from it such that the hull will begin to ease back toward the “on” side. Keep the blade well submerged until the desired correction has been accomplished.

If greater correction is necessary, hold onto that rudder a bit longer, bring the grip inward a bit more, or push the blade outward a bit more or some combination of those three things. The important thing is to be gentle. Increasing the angle, more than a little bit, creates a great deal of resistance and wipes away your forward momentum.

Lift the blade vertically, out of the water, turn your thumb (grip hand) back upward (so that it and the blade are horizontal (parallel to the water) and swing the blade forward to begin the next stroke.

Remember these three points:

The entire correction should be done gently.

Keep blade nearly vertical or perpendicular to the water throughout the correction.

Keep the blade fully submerged.

It all sounds easy and it becomes so with practice but turning the thumb down seems unnatural at first and there is an almost universal tendency to begin lifting the blade, from the water, far too soon. Be gentle and patiently give the canoe time to respond. You’ll be rewarded with a smoother, more efficient ride and far less fatigue at the end of the day.

The following two videos illustrate the proper execution of the J Stroke, the 1st in real time and the 2nd at ¼ speed. When watching, take notice that the blade is kept almost fully submerged, throughout the stroke, that it is nearly vertical (perpendicular to the water surface, and that blade angle is only slight, relative to the keel line of the canoe.

Theme by Out the Box

Fantastic! Couldn’t have been more clear; Thank you!

And also, clarified the position of the blade during the correction, which was where I was originally hung up.

I have watched several videos with paddlers tilting their blade closer to 45 degrees, but I’m assuming that is where the “gentle” correction comes in rather than a “hard” correction.

Is it safe to assume that this will shorten the time the blade needs to be held in the water as well (because the vertical is more effective)?