Actually no, but maybe yes it all depends on how fast you want to turn.

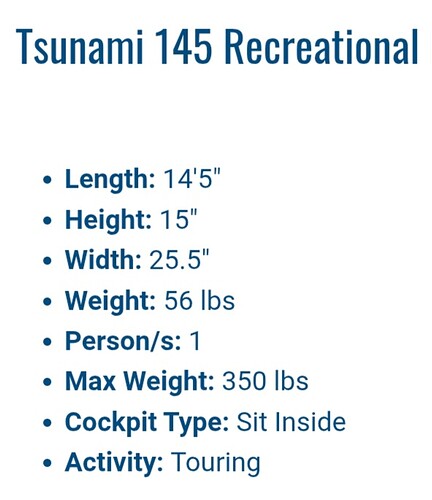

I have a tempest 180 pro and a tsunami 175 (soon to have the pro model.) both boats are within 0.1 Mph of each other based on hull speed so close enough to each other for government work.

So if I ignore wind conditions and relate testing on calm still days as in wind other factors come to play.

The tempest is a faster boat only slightly in straight line, but is much faster in the turn (provided I pull the skeg.) She will out turn the Tsunami without using the rudder.

So what do I mean by that.

With the Tsunami just edging, to initiate a turn the boat will do a 180 in about 17-20 boat lengths. so toe explain from were I initiate the turn to the right I will be 17-18 boat lengths further right by the time I am going in the opposite direction. this is all without using any strokes to initiate a turn (J or Sweep stroke.) There is some speed bleed but much less than using the rudder.

Conversely the Tempest 180 on edge makes that same directional turn in about 10-12 boat lengths. Again there is some speed bleed here as well but both boats seem to bleed the same amount of speed. or near enough so.

This isn’t I suppose really a call out to Skeg v. Rudder, but more a call out to Hard Chine V. Soft Chine.

Most times In less windy conditions I get both boats going straight just by minor weight shift either left or right in the cockpit that keeps the boat going straight. or rather where I want it to go.

The only time I use a turning stroke or rudder is when I need to lessen the turn radius. For racing an turning about the pylons I don’t bother doing this I just aim my course so I’m offset to the pylon by the necessary boat lenghts as I’m making my approach, so that when I begin my edge turn I’m going in the direction i need to be by the end around the pylon. I do this to bleed off the minimum amount of speed though it comes at the cost of traveling slightly farther than any one who tries to make the tightest turn around the pylon.

What I found is that the rudder costs me about 1 mph when deployed, where as the skeg if I need it costs me about 0.2 mph so in either boat unless conditions call for it I’ll try to use neither.

However (and I wish I still had my data that was lost in my phone switch, stupid IT department.) so bear with me on this as the numbers may be off a bit but doing from memory and all. The tempest in calm conditions the max speed I can hit over a 3 mile run (no turns.) is 6.2 mph. The Tsunami on the other hand the max speed is 5.8 mph, but if we add in wind where it’s kicking up 12" chop the Tsunami drops to 5.4 mph and the tempest drops to 5.4 mph as well. (same day same conditions, of quartering chop)

This greater effect I attribute to the soft chine of the Tempest.

But to your point you’re not going to expend more energy trying to maintain speed if you are edging right

no as to conditions when they deteriorate further the the 1mph impact of the rudder isn’t going to really matter one whit, and edging is no longer sufficient a rudder is probably then more energy efficient. as you then only need to concentrate on thrust strokes there’s only so much a skeg can do also over longer distances the impact of the rudder becomes less evident especially in big water.

but for most inland conditions I stand by my observations. .

@Jyak this might help you out to better understand my stroke, I just realized this myself while reading all the posts here. Think of it as a Canoe Oar Stroke but with a double bladed Oar. My catch and follow through are very much like you would make when paddling a canoe, as opposed to a traditional Kayak Stroke. I guess I adopted this form after transitioning from WW Canoe, to WW Kayak, I had by that time already developed the canoe stroke so giving me a kayak and paddle there’s no way you can make this stroke without a 60deg feather.

really the only thing to talk about here is stress to the wrist. the bent shaft allows for the mechanics of the wrist to be in a neutral position through the entirety of the paddle stroke relieving strain on the wrists. Other than that There’s not a heap of the difference I can tell except that they’re going to soak you for more money for your comfort.

And I do apologize I’ve probably explained this all poorly, I’ll bring the tempest and the tsunami one day and let John see the technique for turning I use maybe he can wordsmith it better than I can.